I spent last Friday to Tuesday in Copenhagen, Denmark, where I was invited to speak at the third annual MAD symposium, mad being the Danish word for food. The MAD Symposium is organized by NOMA, the renowned Copenhagen restaurant famous for innovative use of foraged (and fermented) foods, and frequently cited as the best restaurant in the world, run by chef René Redzepi. Though I do not typically follow the international restaurant scene, I started paying attention to Redzepi after he tweeted about my book: “THE (nerdy) food book of the year! Are you ready for microbes crawling on your food?”

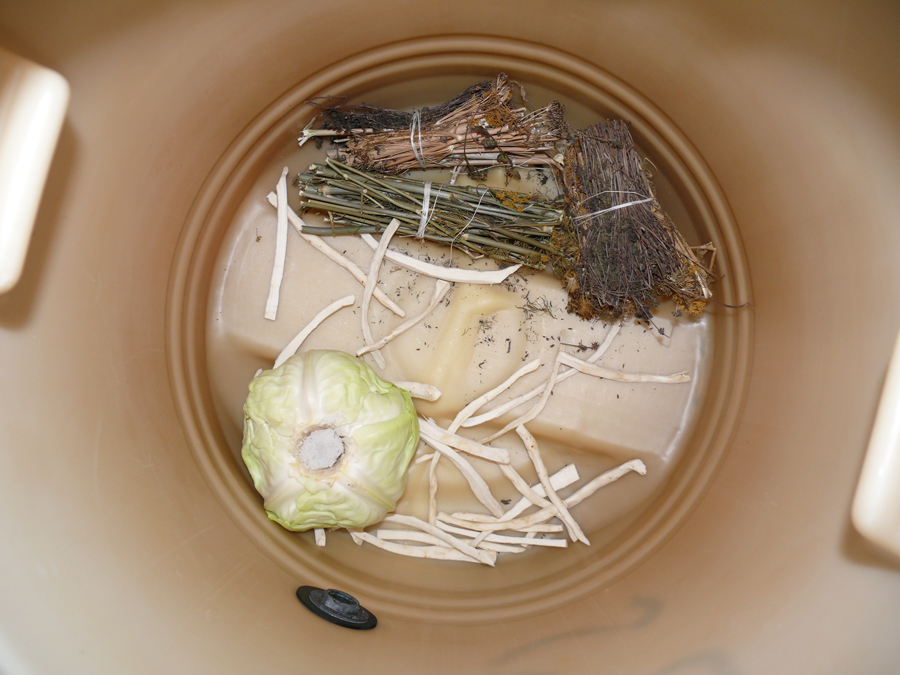

First order of business after my arrival was dinner at NOMA. No menu (until we left, as a souvenir), just small course after small course, each accompanied by wine, so I have no confidence in my count for the evening of 28 courses! I couldn’t write fast enough to both document them all and eat them, and I have my priorities. Virtually every course was a sensation of flavor and texture. Most were fairly simple, with some extremely clever twist. For instance, “Nordic Coconut,” which was a kohlrabi, with a hole bored in the side, and the center hollowed out and filled with lightly fermented kohlrabi juice, and a “straw” made from a hollow plant stem. (Sorry you have to scroll down for photo)

“Nordic Coconut” at NOMA.

“Blackcurrant Berry and Roses” was essentially black currant fruit leather formed into hollow balls, filled with fermented cream, garnished with rose petals and elderflowers, and served on a bed of wild greens.

“Blackcurrant Berry and Roses” at NOMA.

There was fried moss, and flatbread covered with grilled rose petals, pickled and smoked quail eggs, pickled pine leaves, crackers with caramelized milk and thin slices of cod liver, and sourdough crackers with sea urchin and fried duck skin. Perhaps the most gorgeous dish of the night was listed on the menu as simply “Berries and Grilled Vegetables.”

“Berries and Grilled Vegetables” at NOMA.

Many of the courses included unusual stocks, including rhubarb root stock, fennel juice, or the juice pressed from lobsters. Several dishes were seasoned with ants. Ferments were featured in many of the dishes, including cream, pine needles, pears, cherries, and more. With the exception of the wines, as far as I could tell all the food included in the meal was prepared from locally grown, foraged, or sourced ingredients. Many of the dishes were served (and explained) by the chefs, including Redzepi himself. All in all, it was an extraordinary dining experience, and inspirational in demonstrating how extremely simple ingredients can be fashioned in such amazingly creative ways.

Saturday was an outing for the symposium speakers and organizers, to the island of Bornholm. The destination was a surprise. We piled into a bus, which took us to the airport, we got on a small plane for a half-hour flight, and into another bus, which took us to a restaurant (Kadeau) overlooking a gorgeous beach on the Baltic Sea. The chefs among us collaborated on an improvisational dinner, while the rest of us boated, swam in the sea, drank, and got to know one another. The dinner was incredibly delicious, I met fascinating people from faraway places, all with fermentation stories to tell, and then we were whisked back onto the bus, the plane, another bus, and back to our hotel.

Sunday and Monday were the symposium itself. About 600 people gathering under a big tent. The theme was “guts,” in all the literal and metaphorical meanings of the word. We speakers were implored to “say the things that you’ve never dared say before.” The opening was dramatic. When the doors opened, there was a dead pig hanging from a chain, suspended over the stage. The first speaker, Italian butcher Dario Cecchini, walked onto the stage to loud AC/DC and gutted the pig before speaking about his life as a butcher and the necessity of accepting the odor of death. He left the intestines on the rustic log that was a podium, and when my turn to speak came, there was nowhere to place my notes except directly upon them, as I discussed gut bacteria!

Speakers included climate scientists, farmers, foragers, scientists, artists, filmmakers, authors, and lots of chefs. My friend Michael Twitty, an African-American Jewish gay food historian, addressed the topic of culinary justice. The great Vandana Shiva spoke about seeds, patenting life, GMOs, and challenged chefs to take a stand. Cookbook author Diana Kennedy, who is a dynamo at 90 years old, dismissed sous-vide cooking and challenged chefs to get real about sustainability in their practices. My talk about gut bacteria and fermentation was well received. Many of the talks were great, but the highlights for me all involved meeting people. By coincidence, at the same moment, two Colombians who did not know each other, one living in Denmark, the other a culinary student in Spain, approached me with copies of my book to sign. I talked fermentation with chefs from Poland, Finland, South Africa, New Zealand, and many other locales. The lunches were fantastic. One was prepared by a group from Beirut (Lebanon) farmers market Souk el Tayeb; the other by the amazing New York and San Francisco restaurant Mission Chinese. The symposium was really fun for me.

The day after the symposium, I made a pilgrimage to the NOMA test kitchen, and the loosely affiliated Nordic Food Lab. NOMA test kitchen director Lars Williams showed me their technique of fermenting in vacuum-sealed bags, effective at keeping oxygen out and avoiding surface mold, but inevitably bloating from carbon dioxide and occasionally bursting.

Apricots fermenting in vacuum-sealed bags in the NOMA test kitchen.

The Nordic Food Lab is in the harbor right next to the restaurant, in a houseboat. Ben Reade (head of R&D there) and his team kept pulling out interesting things for us to taste. Some notable ferments included unripe plums fermented in a brine that tasted like olives, and garum (Roman fish sauce) from pheasant and rabbit. Beyond ferments, they are doing lots of work on edible insects, and figuring out how to make insect-based foods acceptable to western palates. When Diana Kennedy showed up, she started cooking us Mexican-style grasshoppers, lovely and delicate with a light lemon-garlic seasoning, served alongside a fiery chili sauce.

Diana Kennedy cooking grasshoppers while talking with Ben Reade.

My favorite moment was when a male chef one-third Diana’s age tried to tell her how to do something, and she gave him a look that cut him down to size and shut him up. Staff lunch at the test kitchen was refreshingly down to earth, centered on roasted celeriac and potatoes.

Since those heady days of chef superstars and food porn, I’ve been settling back down to earth, returning to my grind teaching fermentation workshops, at the Copenhagen House of Food, a rural intentional community called Friland, and tomorrow at a farm and cooking school called Fuglebjerggaard. In Denmark, as everywhere, there is a hunger for practical information on fermentation.